Mystery in The Air

After this storm cloud, there came another, which produced only little roses or wheels with six rounded semicircular teeth … which were quite transparent and quite flat … and formed as perfectly and symmetrically as one could possibly imagine. There followed, after this, a further quantity of such wheels joined two by two by an axle, or rather, since at the beginning these axles were quite thick, one could as well have described them as little crystal columns, decorated at each end with a six-petalled rose a little larger than their base. But after that there fell more delicate ones, and often the roses or stars at their ends were unequal. But then there fell shorter and progressively shorter ones until finally these stars completely joined, and fell as joined stars with twelve points or rays, rather long and perfectly symmetrical, in some all equal, in others alternately unequal. (1)

The beauty, symmetry and diversity of snow crystals have long fascinated scientists. Snow crystals come in endless variety of six-fold symmetric shapes, sometimes thinner than a sheet of paper and up to 3 millimeters across. How can they grow in a three dimensional bath and yet be thin? What natural processes could lead to great diversity of shapes that are complex yet symmetric? What keeps opposite sides of the growing crystal in step even as a unique shape is forming? And with slightly different temperature or humidity produces sensible hexagonal columns instead? Is there any rational explanation for the generation of these crystals out of thin air? Can you formulate a hypothesis that even has a chance?

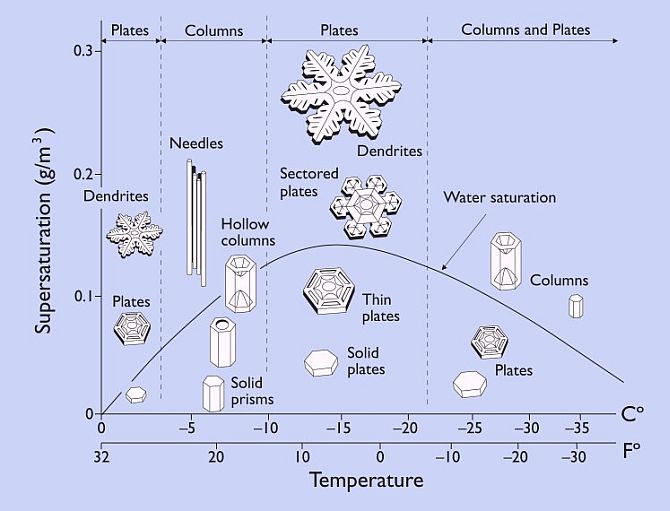

The Japanese scientist Ukichiro Nakaya, working in the nineteen thirties through nineteen fifties was the first one to develop methods to grow individual snow crystals under carefully controlled conditions. (2) Nakaya had intended to be a nuclear physicist, but he got a professorship on the Japanese island of Hokkaido where there no nuclear facilities. There was, however, lots of snow. Nakaya’s 1954 book, Snow Crystals, Natural and Artificial, “…offers a superb look at a scientific investigation which begins with almost nothing, and proceeds through systematic observation toward an accurate description of a fascinating natural phenomenon.” (2) Most of his experimental discoveries are summarized in what is now called the snow crystal morphology diagram.

The morphology diagram does not show all possible types of snow crystals. It shows only shapes that grow under fixed conditions. But knowing both the morphology diagram and that natural snow forms in turbulent storm winds gives us a big boost toward understanding how such diverse yet symmetric shapes are formed. Each crystal follows its own essentially random path through the sky and hence through conditions that will stimulate different sorts of growth, and so gains a different form. Conditions do not vary significantly over the size of a crystal though. So each crystal takes on a different symmetric form.

Nakaya’s work beautifully lays out the snow crystal puzzle. Now all we have to do is solve it. In very broad terms snow crystals happen the way other things happen in nature, especially things with complex symmetry.  They result from a combination of natural regularities, surprising threshold effects, and a sequence of frozen accidents. But what are the regularities and nonlinearites? How does it happen, for instance, that at a supersaturation of around .1 g per cubic meter, crystals are (with decreasing temperature) hexagonal plates, then columns, then plates, then columns again? How can the morphology diagram be explained?

They result from a combination of natural regularities, surprising threshold effects, and a sequence of frozen accidents. But what are the regularities and nonlinearites? How does it happen, for instance, that at a supersaturation of around .1 g per cubic meter, crystals are (with decreasing temperature) hexagonal plates, then columns, then plates, then columns again? How can the morphology diagram be explained?

This is what physicist Ken Libbrecht is trying to find out. While Christmas shopping last month I couldn’t help noticing the beautiful snow crystal on the cover of the new American Scientist. This led me to Libbrecht’s article The Formation of Snow Crystals (3). The article was quite intriguing, but there was a key point I couldn’t follow. On page 57 he seems to say that his experimental measurements of the growth velocity of different facets were contrary to what the morphology diagram predicts, yet the diagram is still correct. How could this be? This led me to read his The Physics of Snow Crystals (4), a mere forty pages with one or two equations, and then another paper with actual data (5). Finally I gained some idea of what’s going on.

But to begin at the beginning: warm moist air rises and rises until it expands and cools. Cold air can hold less water vapor than warm air, and so, especially if the air becomes very cold, it will become supersaturated with water vapor. Air is full of vast numbers of tiny dust particles; very tiny water droplets form on these particles. Even well below the normal freezing point, these droplets do not freeze into ice, but instead most persist as supercooled water. Different ones freeze at different temperatures, due in part to the surface characteristics of their dust particle. Those that freeze may grow into snow.

The minute supercooled liquid droplets have so much surface area in relation to their volume that they are constantly evaporating and reforming. Once a vapor molecule sticks to an ice crystal, though, it tends to stay there. Thus the crystals grow at the expense of the droplets. The droplets are so small that a good sized snow crystal may have consumed a million of them (3:52). To a first approximation, crystal growth is diffusion limited A growing crystal uses up nearby vapor molecules and cannot grow larger until more vapor diffuses to it.

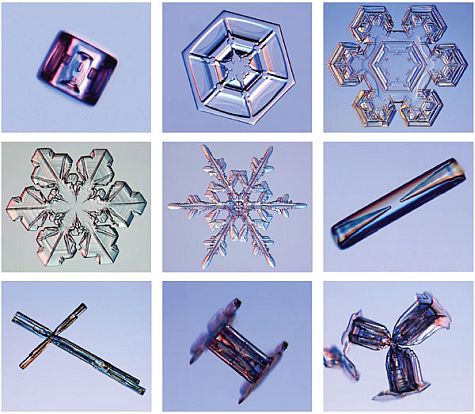

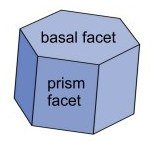

Early in its growth nearly every snow crystal experiences faceting. This is a normal feature of crystal growth in which rough spots smooth out and the crystal takes on a characteristic shape with several plane faces, or facets. For ice crystals in normal winter conditions, this shape is a hexagonal prism.

Early in its growth nearly every snow crystal experiences faceting. This is a normal feature of crystal growth in which rough spots smooth out and the crystal takes on a characteristic shape with several plane faces, or facets. For ice crystals in normal winter conditions, this shape is a hexagonal prism.

Growth of the crystal facets. Once a crystal takes on this basic shape, growth tends to be normal to the facets, at least as long as growth is not too fast and the crystal is not too large, say less than half a millimeter across. Growth is controlled by attachment kinetics, which is in turn controlled by the still mysterious surface physics of the growing snow crystal.

Modern equipment makes possible measurements Nakaya couldn’t make, including the growth rate of individual facets. This measurement is important because of its quantitative relation to other factors. But it isn’t easy: “… a critical examination of the literature reveals that essentially all the results published to date suffered from systematic errors to some degree.” (4:878) On the basis of recent measurements though, Libbrecht suspects that growing snow exhibits a previously unknown type of instability - which brings me back to the unexpected data I mentioned earlier.

Low pressure is the key - to normal crystal growth. When grown at -15 degrees Centigrade and high supersaturation, right where the morphology diagram predicts the thinnest crystals, but at less than one quarter of normal atmospheric pressure, all the facets grow at about the same very slow rate and the crystals look blocky and ordinary. But merely increase the pressure and the prism facets (but not the basal facets) start growing up to 50 times faster! How can ordinary air have this effect? Libbrecht gives a very partial explanation in (5): a thin but growing facet is expected to have a parabolically curved edge, with a small radius of curvature. The radius is inversely proportional to pressure according to a certain formula that can be derived with some simplifying assumptions. Compared to a flat crystal surface, this curved surface will be rough on a molecular scale. This makes it easier for some ice molecules to form hydrogen bonds with passing vapor molecules and hold on to them. Evidently, when there is enough pressure, and hence enough curvature, growth becomes much faster. Libbrecht refers to this as a knife edge instability resulting from structure-dependent attachment kinetics.

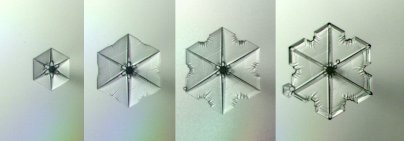

As Libbrecht says, “This is a speculative model, without a strong theoretical foundation, so additional work is needed to understand this aspect of the growth dynamics.” (4:881) But as he explains, the knife edge instability is consistent with both the crystal growth data at different pressures and notable features of natural snow. These features include the extreme thinness of large stellar crystals (about .01 millimeter) and the abrupt transition observed in capped columns (see the first illustration). “… instabilities tend to amplify small changes in initial conditions. If the local environment changes just slightly to prefer platelike growth over columnar growth, then the instability kicks in to immediately produce thin plates.” (3:58)

Branching and dendritic growth. Growing perpendicular to the facets is not the only way snow grows. Snow crystals are famous for their complex branched and dendritic forms. This type of growth too has been modeled and studied experimentally. As each crystal facet expands, its center is slightly starved of vapor molecules compared to its corners. This makes the facet just slightly convex although it looks flat to the eye. The convexity, greatest at the center, amounts to roughness on the molecular scale - the scale where the action is. This roughness leads to a little greater percentage of incident vapor molecules sticking to the crystal, and so the center’s growth keeps up with the corners - until it doesn’t. When the crystal is large enough, say about half a millimeter across, and/or growth is fast enough, branches spout from the six corners of the hexagon. This is called the Mullins - Sekera instability, or simply the branching instability.

The corner branches may become long dendrites; these may sprout dendrites of their own, or in other conditions may even sprout six new flat plates. A dendrite’s rate of elongation, and hence rate of vapor consumption, may become so great that the growing tip is in a region of reduced vapor density. Nonetheless the highly curved, and hence molecularly rough, tip keeps on growing. Dendritic growth is observed in other sorts of crystals and is thought to be fairly well understood. Snow crystal branches and dendrites are unusual, though, in that they retain their basal non-growing facets. Faceted dendrites are not so well understood. (4)

Has the challenge of the morphology diagram been met? There is reason for optimism about future research. The identification of systematic errors in previous experimental data should result in more precise data in the future, and the structure-dependent attachment kinetics hypothesis is a promising lead. But for now, the explanation (above) of capped columns, for instance, includes these words: “If the local environment changes just slightly to prefer platelike growth over columnar growth ….” But why would a slight change in conditions have this effect? That was the question. In the end Libbrecht admits

The growth of plain hexagonal ice prisms remains perhaps the most puzzling aspect of snow crystal growth, in spite of its apparent simplicity. The snow crystal morphology diagram, well documented now for 75 years, has still not been explained at even a qualitative level. (4:891)

Mystery is still in the air.

============================================================= Acknowledgment

All the illustrations except the pine lily are courtesy of Ken Libbrecht with permission.

============================================================= Activities and additional reading

Get to Ken Libbrecht’s www.snowcrystals.com to find lots of activities, movies and books on snow crystals. There is no snow in my neighborhood, but I’m interested in hearing your experiences. Can anyone match Descartes’ observations, even with the help of a hand magnifier?

Meteorological background: Snow Formation in the Atmosphere

Snow Flakes and cellular automata

============================================================= References

-

René Descartes 1637. Les Météores (a series of essays attached to his Discours de la Methode), as cited in The Snowflake: Winter’s Secret Beauty – by Kenneth Libbrecht and Patricia Rasmussen.

-

www.snowcrystals.com

-

Libbrecht KG 2006. The Formation of Snow Crystals. American Scientist (95:1, 52-59). online

-

Libbrecht KG 2005. The physics of snow crystals. Reports on Progress in Physics 68 (2005) 855–895. online

-

Libbrecht KG 2003. Explaining the Formation of Thin Ice-Crystal Plates with Structure-Dependent Attachment Kinetics. J. Cryst. Growth 258, 168-175. online