Nelson vs Mycoplasma: ORFans redux.

Paul Nelson has developed a liking for ORFans, sequences of DNA that appear to code for proteins, but have (or had) no currently detectable homology to other genes. He feels they represent a difficulty for “Darwinian” accounts of gene origin and common descent. I have previously discussed why ORFans present no challenge to modern evolutionary theory, Dr. Nelson even showed up in the discussion.

More recently, he has been promoting ORFans again, without indicating he has learnt anything at all from our discussion. In particular, in a recent article in the Christian Post he claims that 28% of the genes in Mycoplasma genitalium are ORFans.

Nearly one-third of the protein-coding genes of mycoplasma, the simplest “free-living thing” up until last year, are unknown genes or ORFans.

Unfortunately for him, the actual number is zero. Yes, that’s right, zero. How did he get it so wrong?

Let me repeat that again. The number of ORFans in Mycoplasma genitalium is zero (Siew et al 2003). What Nelson has done is confused two entirely different concepts, and it doesn’t help his case at all.

The papers Nelson is thinking of look at the number of essential genes in the bacterium Mycoplasma genitalium (Glass et al., 2006, Hutchison et al 1999). M. genitalium has one of the smallest genomes known for a bacterium that can be grown in pure culture, with only 482 protein coding genes. What these papers did was systematically mutate these genes to find out which ones were truly essential. They found that 382 of the 482 protein coding genes were essential. However:

“One of the surprises about the essential gene set is its inclusion of 110 hypothetical proteins and proteins of unknown function. Some of these genes likely encode enzymes with activities reported in M. genitalium, such as transaldolase (21), but for which no gene has yet been annotated.” (Glass et al., 2006)

That is, roughly 28% of the proteins in the essential set are proteins of unknown function. Here is where Nelson makes his mistake. He equates proteins having an unknown function with being an ORFan (having no known homology with other genes). And this is just wrong.

In fact, there are large families of proteins of unknown function that are found in nearly all organisms studied. They form perfectly good phylogenies, we just don’t know what they do (Galperin & Koonin 2004). For example the E. coli gene ybeM has homologs in 52 other organisms, from yeast to humans, and is a member of the nitrilase family, but we just don’t know what it does. This is diametrically opposed to what Nelson wants to claim, that there are large number of genes that have no apparent ancestors.

“Where are the similar sequences that gave rise to these ORFan genes? Where are the necessary intermediates that must have been there? Where are the parents, if you will, of these mysterious genetic words?”

What probably got Nelson confused was that 28% of M. genitalium putative protein coding genes were orphans when the M. genitalium genome was first reported. The percentage of unknown protein coding genes is also 28%. The same figures, but completely different concepts.

Unfortunately for Nelson, by 2003 homologs for all the putative protein coding genes had been found (Siew et al., 2003). Those similar percentages, possibly with help from Morton’s Demon , caused Nelson to confabulate the two separate concepts, genes with no apparent homologs (ORFans) and genes with unknown function*.

This is an object lesson in reading research papers carefully.

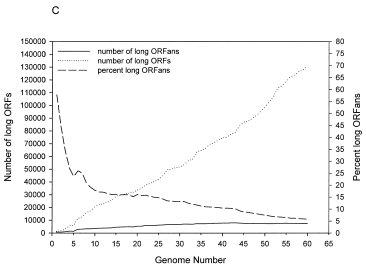

Another aspect Nelson keeps on misrepresenting is the numbers of ORFans. As we sample more genomes, the numbers of ORFans rise. But, because we are finding many more known genes, and finding relatives for genes that were previously ORFans, the percentage of ORFans is decreasing. The figure below (Taken from Siew et al., 2003) shows this. The dots represent the number of protein coding genes that we are finding, the sold line is the number of ORFans we are finding, and the dashed line is the percentage of ORFans we have found.

Clearly, as time goes on, we are finding more and more relatives for the ORFans (in 2003, the number of protein coding ORFans was around 5%#, by 2005 (Wilson et al 2005), it was down to 1.2%. Unfortunately for Nelson, we are finding the alleged “missing parents” of the ORFans+. And this is with only a fractionally minute sampling of the diversity of microbial life (we have sampled only 0.02% of all bacterial genomes, and we are biased towards a subset of human pathogens at that).

Back in April I issued the following challenge to Paul Nelson

I would also assume, in respect for scholarly accuracy, that in your next talks you will show the exponential decrease in percentage ORFans, as well as the increase in number, as well as mentioning the experimental tests of hypotheses about ORFans that have been under taken and their results.

He hasn’t done that as yet, and I issue the challenge again Paul. Show the exponential decrease graphs and mention how biologists are testing hypotheses about ORFans.

Oh, and don’t conflate “unknown function” with ORFan.

Update: Just to make my point, I’ve gone through the essential unknown function and hypothetical proteins in M. genetalium by hand (see table 2 in the Supporting documents of the Glass et al., 2006 paper). They are present in large to modest families, not ORFans.

| For example MG125 (white bar in Fig 2 of Glass et al., 2006), is of unknown function, but is a member of the Cof hydrolase family, and has many [ homologs in a wide variety of bacteria ](http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/treeview/blast_tree_view.cgi?request=page&rid=1164068750-12935-24648474209.BLASTQ4&dbname=nr&queryID=gi | 12044977&distmode=on). MG442 is a conserved hypothetical protein of unknown function that has [similarities to GTPase enzymes](http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/treeview/blast_tree_view.cgi?request=page&rid=1164099696-18115-181293974365.BLASTQ4&dbname=nr&queryID=gi | 12045301&distmode=on&screenWidth=1280), but we still don’t know what it does. MG461, HD domain protein of unknown function, but with [widely distributed homolgs](http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/treeview/blast_tree_view.cgi?request=page&rid=1164100061-28260-157458926616.BLASTQ4&dbname=nr&queryID=gi | 12045320&distmode=on&screenWidth=1280). MG459 a conserved hypothetical protein of unknown function with many homologs in other bacteria, similar in structure to MECDP_synthase. MG074 is a conserved hypothetical similar to trichodiene synthase in a number of bacteria. |

And so on. You can do this for yourself, Paul Nelson could have done it himself after I alerted him to the problem back in April. Of the 110 “unknowns” 65 are from systems which have good phylogenies, and known relations to function proteins, but we just don’t know what they do yet, 45 are conserved hypothetical proteins, where we don’t even have structural clues to function yet. But note the “conserved”, that’s because they are found in a wide variety of organisms.

Bottom line: not ORFans.

Update to the Update: I have created a table with BLAST tree views of the 45 conserved hypothetical proteins, it turns out that many of them either are members of Clusters of Orthologous Groups (ie parts of an extened family, for example MG337 is a member of COG0822C) or close to members of COG’s (Like MG101, which has a HTH_GTNR domain and appears to be related to transcrition factors). Anyway, if you want a copy of the table, with hyperlinks to the trees and COGs, go to Southern Skywatch Feedback and click on the email address there. The Treeviews can be misleading, as they don’t show all the related proteins (click on the show removed sequences link to see the more distant relatives). I’m off to the Australian Health and Medical Research Congress for a week, so I’m turning of the comments while I’m away, as I won’t be able to moderate. Sorry.

*ORFans and proteins with unknown function can of course coincide, but in this case they don’t #I’m ignoring the small ORFans, most of which are likely artefacts or bits of viral DNA, see my original post for details and Daubin & Ochman 2004.

-

Finding relatives is not necessarily easy, but the recent solution of crystal structure for ORFans is greatly increasing our ability to find relatives (eg Siew et al, 2005).

- Daubin V, Ochman H. Bacterial genomes as new gene homes: the genealogy of ORFans in E. coli. Genome Res. 2004 Jun;14(6):1036-42.

- Galperin MY, Koonin EV ‘Conserved hypothetical’ proteins: prioritization of targets for experimental study (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 5452-5463

- Glass JI, et al Essential genes of a minimal bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Jan 10;103(2):425-30.

- Hutchison CA, et al., Global transposon mutagenesis and a minimal Mycoplasma genome. Science. 1999 Dec 10;286(5447):2165-9.

- Siew N, Fischer D. Analysis of singleton ORFans in fully sequenced microbial genomes. Proteins. 2003 Nov 1;53(2):241-51

- Siew N, Saini HK, Fischer D. A putative novel alpha/beta hydrolase ORFan family in Bacillus. FEBS Lett. 2005 Jun 6;579(14):3175-82.